In the early 1880s the British-backed Egyptian regime in the Sudan was threatened by an indigenous rebellion under the leadership of Muhammed Ahmed, known to his followers as the Mahdi. In 1883 the Egyptian government, with British acquiescence, sent an army south to crush the revolt. Instead of destroying the Mahdi's forces, the Egyptians were soundly defeated, leaving their government with the problem of extricating the survivors.

The difficulties of evacuating their forces in the face of a hostile enemy quickly became apparent, and the British were persuaded to send General Charles Gordon, already a figure of heroic proportions in England, to consider the means by which the Egyptian troops could be safely withdrawn. Disregarding his instructions, Gordon sought instead to delay the evacuation and defeat the Mahdi.

The relief force was sent from Cairo in September 1884, but it was still fighting its way up the Nile when Gordon was killed in late January the following year. Gordon's exploits were well known throughout the British Empire, and when the telegraph brought word of his death to New South Wales in February 1885 it was met with recriminations against the Liberal government led by William Gladstone for having failed to act in time.

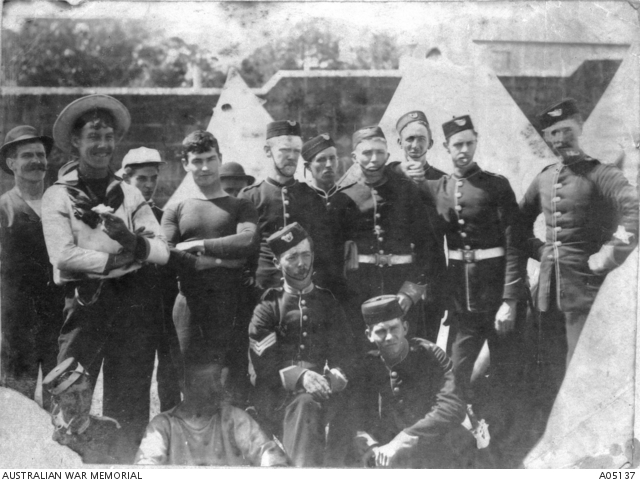

Volunteers for the NSW Infantry Contingent for the Sudan at Victoria Barracks, Sydney, shortly before the contingent's departure on 3 March 1885

With news of Gordon's death and the Canadian government's offer of troops for the Sudan, the NSW government cabled London with its own offer. To make its proposal more attractive, it offered to meet the contingent's expenses. London accepted but stipulated that the contingent would be under British command. Similar offers from the other Australian colonies were declined. The British government's acceptance of the contingent was received with enthusiasm by the NSW government and members of the armed forces. It was seen as a historic occasion, marking the first time that soldiers in the pay of a self-governing Australian colony were to fight in an imperial war.

Sydney, 3 March 1885. Departure of the NSW Contingent for the Sudan

The contingent, an infantry battalion of 522 men and 24 officers, and an artillery battery of 212 men, was ready to sail on 3 March 1885. It left Sydney amid much public fanfare, generated in part by the holiday declared to farewell the troops. The send-off was described as the most festive occasion in the colony's history. Support was not, however, universal, and many viewed the proceedings with indifference or even hostility. The nationalist Bulletin ridiculed the contingent both before and after its return.

The NSW contingent anchored at Suakin, Sudan's Red Sea port, on 29 March 1885 and were attached to a brigade composed of Scots, Grenadiers, and Coldstream Guards. Shortly after their arrival they marched as part of a large square formation – on this occasion made up of 10,000 men – for Tamai, a village some 30 kilometres inland. Although the march was marked only by minor skirmishing, the men saw something of the reality of war as they halted among the dead from a battle which had taken place 11 days before.

.

After Tamai, the greater part of the NSW contingent worked on the railway line which was being laid across the desert towards the inland town of Berber on the Nile, half-way between Suakin and Khartoum. When a camel corps was raised, 50 men volunteered immediately. On 6 May they rode on a reconnaissance to Takdul, 28 kilometres from Suakin, again hoping for an encounter with the Sudanese, but the only action that day involved two newspaper correspondents who had accompanied the patrol before leaving the cameleers to file their stories in Suakin. They soon found themselves surrounded by enemy forces, and one was wounded as they fled. The camel corps made only one more sortie – on 15 May, to bury the bodies of men killed in fighting the previous March. On 15 May they rejoined the camp at Suakin. Not having participated in any battles, Australian casualties were few: those who died fell to disease rather than enemy action. By May 1885 the British government had decided to abandon the campaign and left only a garrison in Suakin. The Australian contingent sailed for home on 17 May 1885.

The contingent arrived in Sydney on 19 June. They were expecting to land at Port Jackson and were surprised to disembark at the quarantine station on North Head near Manly as a precaution against disease. One man died of typhoid there before the contingent was released. Five days after their arrival in Sydney the contingent, dressed in their khaki uniforms, marched through the city to a reception at Victoria Barracks where they stood in pouring rain as a number of public figures, including the Governor, Lord Loftus, the premier, and the commandant of the contingent, Colonel Richardson, gave speeches.

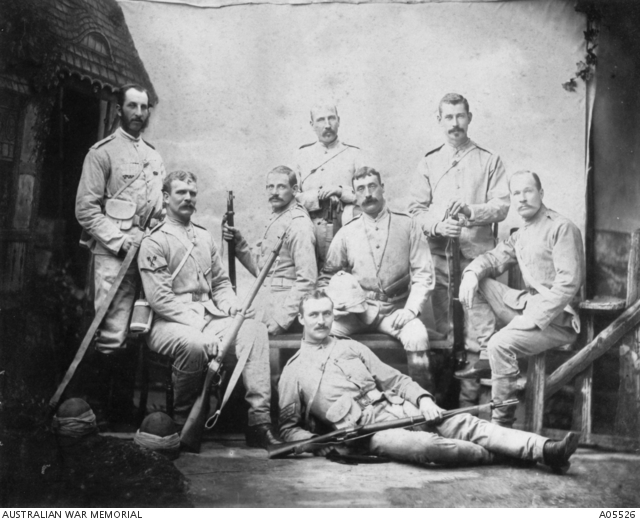

Sydney, NSW, 1885: infantrymen of the NSW Contingent to the Sudan, after their return to Australia. They are wearing khaki uniform issued for active service, and are equipped with Martini-Henry rifles.

References:

K. I. Inglis, The rehearsal: Australians in the Sudan, 1885, Sydney, Kevin Weldon and Associates, 1985

Peter Stanley (ed.), But little glory: the New South Wales contingent to the Sudan, 1885, Canberra, Military Historical Society of Australia, 1985

Ralph Sutton, Soldiers of the Queen: war in the Soudan, Sydney, New South Wales Military Historical Society and the Royal New South Wales Regiment, 1985

Source: www.awm.gov.au/articles/atwar/sudan (accessed 13 June 2019)